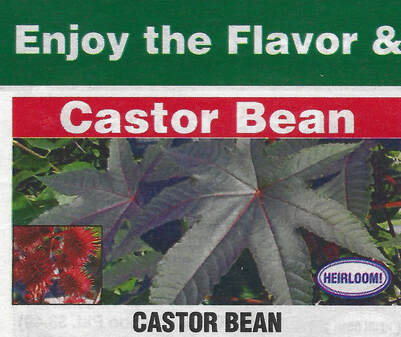

Making lifelong progress as a gardener (From the current issue of Colorado Gardener magazine) When I was a kid, we had a horse for a while. Chico, a handsome palomino, was really my sister’s love, but I was signed up for lessons. We practiced looping around barrels, weaving through slalom poles, and other maneuvers that neither of us understood the point of. Chico was so unconvinced of the need for these activities that once, instead of going in the direction I was tugging the reins, he just casually walked back into the barn, scraping me off the saddle as he passed under the low doorway. I also lacked passion and confidence, so I never developed good riding skills. Recently, I read about some historical figure – I think it was Winston Churchill, or possibly Johnny Depp – who attributed much of his success in life to the discipline and confidence gained from becoming an expert equestrian in his youth. This made me wish I had put in more effort at learning to steer Chico so I could stick the flag in the bucket faster. I should have listened to my grandmother, who predicted with eerie prescience way back then that if I didn’t work hard, I wouldn’t amount to a row of pins. Since I wasn’t progressing much in horsemanship, they kept putting me in the beginner class again each summer. Eventually, from sheer experience I got to the point where I won most of the ribbons in the end-of-season tournament at the county fairgrounds. In retrospect, it was unfair for me, with several years of albeit uninspired riding under my big silver belt buckle, to compete with novices. But Chico and I were young and didn’t realize this at the time, so we basked in our glory. That was almost 50 years ago now. I haven’t been on horseback much since, but I still spend many hours every summer in a field, lazily striving for success. I worry I’ve been gardening the same way I rode the horse: taking the easy way, not putting in enough time with the stirrup then and the stirrup hoe now, never pushing myself to improve. The easy success of beginner-level gardening can lead to complacency. Growing huge crops of zucchini, peas, and especially leafy greens takes no great skill. With nicknames like dinosaur kale, they have Jurassic toughness. Nothing short of an asteroid can kill them. Nevertheless, I stride into the kitchen brandishing giant chard leaves with the same unearned pride I got from those horse show ribbons. I always grow some intermediate plants too, like tomatoes and peppers. But I’ve become accustomed to mediocre yields, just a few fruits on each plant to show for months of watering and weeding. Surely I could reap much bigger harvests if I worked harder to learn their needs and desires. Instead of haphazardly scattering compost, I could test the soil and precisely amend it with their favorite flavors of micronutrients. I could spend winter evenings designing optimal crop rotation schemes rather than carrying my seedlings out to the beds each spring and trying to remember what I planted where last season. At just the right times throughout the summer, I could prune the suckers, side dress with eggshells and fish goop, and sing to the veggies as Prince Charles recommends. (He even asked Katy Perry to serenade his plants during a garden tour!) I lack the discipline to do these things consistently, and I don’t know any pop stars, but it’s good to have theoretical goals to shoot for. Beyond this level are the advanced vegetables that I’ve been too intimidated even to try. I don’t have the confidence to think I can successfully shepherd artichokes or Brussels sprouts through their long growing season without being annihilated by aphids long before maturity. But through hard work I could probably learn to do that, and to tie up cauliflower leaves and trench celery. Maybe someday I’ll even tend trays of Belgian endive in my dark basement! I’m determined to do better. I feel I have something to prove. To the Belgians, mainly, with their tricky sprouts and endives, but also to myself. It's never too late for self-improvement. To move up from beginner level in anything, you must be open to new ideas and question the old ways. Standard sources of information can be dangerously inaccurate. In one seed catalog I received this spring, a big banner at the top of a page blares “Enjoy the Flavor and Nutrition!”, but right under it is the ad for castor beans. That makes the headline seem less like a persuasive sales pitch and more like something Walter White would sneer as he slipped ricin into your tea. Good garden tips await us in quite unexpected places. Speaking of horses, another thing that happened 50 years ago was the release of The Godfather. This classic film is beloved for its insights about power, family, loyalty, and, most importantly, gardening. I rewatched it last year and was thunderstruck when Vito Corleone, the retired mafia don played by Marlon Brando, suffered a (spoiler alert!) fatal heart attack while playing with his grandson in the garden. It wasn’t the plot twist that shocked me. I barely noticed that, because I was transfixed by the beautiful 8-foot tomato vines climbing poles just a couple feet apart in a dense grid. I had always used the small round tomato cages, which work okay for bush varieties like Roma. But I prefer the big slicers, whose long indeterminate vines overwhelm those flimsy supports. Last season I switched to the Godfather’s garden system, minus the armed goons at the gate, with excellent results. Plus, now I can proudly describe my tomatoes as “cage free”! With this steady improvement in my gardening knowledge, I expect to finally graduate out of the beginner category and enjoy increasing yields for years to come, while remaining mindful that with greater rewards come greater risks. Remember, after a long career as a ruthless mob boss, surviving all manner of intrigues and assassination attempts, what finally whacked Don Corleone? The garden! ________________________ I hear that even Instragram is now just for old people. So if you are old like me (or old at heart, I guess?), please join me for more garden humor on Instagram at johnmhershey.”

0 Comments

I've been gardening for years, and this is the first time I've come across this particular hot pepper variety. Speaking of which, my article in the current issue of Colorado Gardener magazine is about how we should all pee in our gardens. To read it online, visit the Colorado Gardener website.

My story "The Salad Days", originally published in Colorado Gardener magazine, appears in the Autumn issue of GreenPrints, the national digest of garden writing. If you've never read this lovely magazine, please check it out.  The community garden in Denver where I learned to garden is going away. It's on the site of an old school ball field that has been sold off for development. Barb, the garden leader, saved as a memento the sign that hung on the backstop overlooking the garden: "No Hardball Allowed." This reminded me that I wrote an article about that sign a few years ago. Here it is. Thanks for reading! No Hardball Allowed

by John Hershey Autumn in the garden puts me in a pensive mood. I spent countless hours out here this season, without much to show for it except a handful of radishes, a few measly wheelbarrows full of zucchini, and some tomatoes that deliberately stayed green just to spite me. As I hauled the brown remains of my lush garden to the compost pile, I began to wonder if it was really worth all the time and energy. Lost in thought, I glanced up and saw something I had never really noticed before: a rusty old sign hanging on the fence. Our community garden is located on the site of an old elementary school ball field. The school building is hip urban lofts now, but the backstop still forms the corner of our garden. The paint is chipped and scratched, but the sign is still legible: "No hardball allowed". I'm sure I've seen it up there before, but I never gave it a second thought, because I read it literally: The kids who played baseball here a generation ago were supposed to use a soft rubbery ball so it wouldn't hurt too much if they got beaned. I thought about climbing up there and taking the eyesore down. But suddenly the words seemed appropriate for the garden too. Our society encourages us to play metaphorical hardball in many situations. "Playing hardball" means being tough, aggressive, competitive, and therefore successful in business, politics, or any other field. When you play hardball, you're forceful and uncompromising, relentlessly seeking the advantage for yourself. Surely there is a place for this approach to life. Society benefits when we all try hard and do our best. Without the freedom to create and reap the benefit, we might not have so many of the things that make our lives better, like computers, medical technologies, and disposable razors with four blades, which we'll just have to make do with until a scientific breakthrough finally gives us the elusive 5-blade razor. And just think how our nation's hardball foreign policy has allowed us to impose stability and democracy around the… OK, forget that one. That's a bad example. Hardball is even the name of a popular TV talk show, on which politicians and pundits yell at each other for the edification of us all. But for all these benefits of playing hardball, we also need skills of cooperation. Sometimes everyone benefits when we work together, sharing resources and helping each other. The community garden is a place to learn these skills. And teach them to our kids. Early this summer, my two young sons and I planted two summer squash seeds on a little mound. At the time, I might have wondered if all the hours we'd spend watering and weeding these plants, just to grow something we could get for less than a buck at the farmers' market, was the best way to spend my precious free time. Is gardening really as productive and worthwhile as other things people do on Saturdays, like playing golf, say, or watching golf on TV? But now I realize it's not really about the food we grow. It's about working together with each other and with Mother Nature. A community garden is not just a garden for the community. It's also a community of gardeners. I know that sounds like a bunch of touchy feely yada blah blah mumbo jumbledegook. But it's true, as this actual anecdote will illustrate. This spring, I started many kinds of seeds indoors in round peat pellets, including two kinds of basil -- the common sweet basil, and another more exotic, pointy-leafed variety. We transplanted the seedlings in the garden, and just weeks later, we began to harvest basil leaves for homemade pesto sauce. The sweet basil pesto was familiar and delicious. But I found the other type of basil rather bland. When I mentioned this to one of my fellow community gardeners, she pointed to the yellow flowers just beginning to appear and informed me that this was in fact not basil but a tomatillo plant, the leaves of which are toxic. I guess the little pots I started the seeds in floated around in the tray and got mixed up. Here I am trying to grow healthy food for my wife and kids, and they're lucky if I don't poison them. We're all lucky I have my fellow gardeners to protect me (and my family) from myself. In the garden, we have a similar cooperative relationship with the earth itself. We're not trying to subdue nature and extract everything we can. Instead, we nurture the soil, making and adding compost in imitation of nature's own cycle of fertility. In this way, my boys see that our relationship with our garden plants is mutually beneficial. Right up until, you know, we pluck them from the ground and devour them. We don't play hardball in the garden. Like the kids who played on this field long ago, we're just out here to have fun. Nobody loses, and if we water our vines we'll all get beaned. A couple weeks later, I read the yellow squash seed packet again. It said I had to keep the strongest seedling and remove the other one. So much for being noncompetitive. Our plants were struggling to outperform each other in a life-or-death game of hardball, and I was forced into the role of umpire. My 6-year-old son Henry was heartbroken when I pulled out the extra plant. "But Dad," he said sadly, "it already had blossoms on it." I guess my kids are learning some lessons out here that I hadn't counted on. But the fact that he was so upset shows how much he cares for all living things. Perhaps gardening has played a role in reinforcing his natural good-heartedness. So I left the sign on the fence. "No Hardball Allowed" is still a good motto for a community garden. To add to the vast archive on Vegetable Husbandry, your trusted source for garden humor, here's an autumn-appropriate article that appeared in the San Francisco Chronicle a few years back: The Beer Garden. Thanks for reading!

Thanks for visiting this blog, presumably having followed the link in Colorado Gardener magazine. In case you'd like to read more mildly amusing adventures in gardening, I thought I'd post some links to articles from the past. Let's start with some not very helpful advice about sneaking healthy garden produce into your kids' food, published in the San Francisco Chronicle way back in 2007:

http://www.sfchronicle.com/homeandgarden/article/How-to-sneak-homegrown-harvest-into-family-dining-2502309.php My story, The Salad Days, appears in the current issue of Colorado Gardener magazine. Here's the link: www.coloradogardener.com

Welcome to Vegetable Husbandry, the garden humor blog! In these troubled times, it has been determined that what the world really needs now, more than anything, is another gardening blog. So here it is. But Vegetable Husbandry is different from all the other garden blogs. How? Well, this blog will contain no useful gardening information whatsoever. That's my promise to you, the reader. Here you will find nothing but mildly amusing observations about raising vegetables and kids on a little suburban homestead. Thanks for visiting!

|

AuthorVegetable Husbandry features garden humor writing by John Hershey <[email protected]>. Archives

April 2022

Categories

All

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed